The Digitorial® for the exhibition

27.11.2024 - 23.3.2025

Amsterdam in the 17th century – bustling metropolis and envy of Europe. The economy and commerce are booming; the population is exploding; art and science are flourishing. Shaping the fortunes of the city is an affluent elite of burghers – captured in numerous paintings by the leading Dutch artists of the age. Amsterdam’s group portraits reflect the pride and self-image of the urban elite. But how do we view that ‘Golden Age’ today?

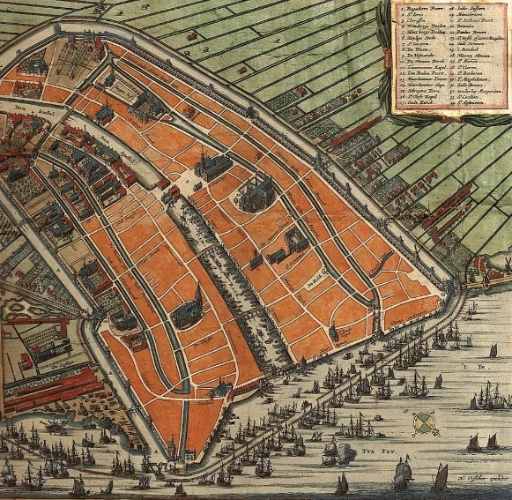

Limited space, scant natural resources, few inhabitants: there was little to suggest that the young Dutch Republic (or ‘Republic of United Provinces of the Netherlands’) would rise to great wealth and power in the 17th century. And yet, within just a few decades, it did just that. And one city in Holland rose to become the leading centre of international trade.

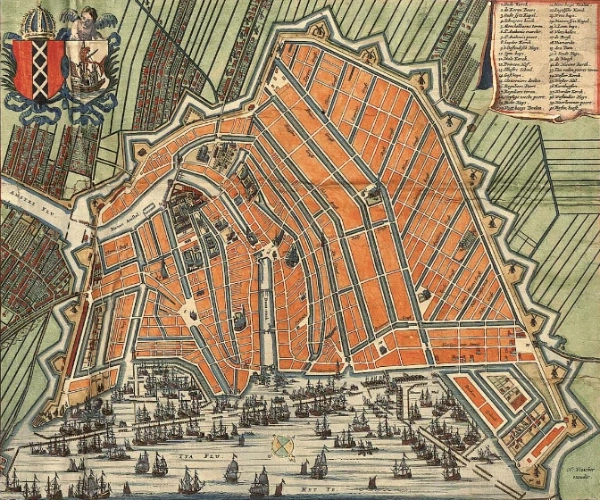

The Stedenmaagd, the personification of the City of Amsterdam, proudly presents the map of the city’s ambitious Fourth Expansion as a gathering of classical gods looks on favourably. An overflowing horn of plenty is scooped from the water – all the world’s riches come from the sea.

As men used to say that there was a land flowing with milk and honey, so it truly is [...] here in Amsterdam.

Melchior Fokkens, 1665

In just 250 years, Amsterdam was catapulted from being a mere fishing village to the centre of global trade. The twin prospect of work as well as political and religious freedom attracted tens of thousands of people. Plying the new maritime routes, they brought goods from all over the world to Amsterdam.

Amsterdam’s rise culminated in its revolt against the Spanish Crown. The city’s most powerful families had long converted to Calvinism. However, the Reformed Church banned religious paintings as idolatrous. This kindled an interest in new forms of art – portraits of prosperous burghers, city views and scenes of everyday life are created.

Change of Power in Amsterdam

Amsterdam was bursting at the seams. Between 1600 and 1662, the number of inhabitants grew explosively from 40,000 to 210,000. The city was to be enlarged by a third in the north-west.

Calvinist virtues such as discipline, diligence and hard work became the basis for Amsterdam's economic success – because prosperity was seen as a sign of divine election. Johann Lingelbach, who was born in Frankfurt, also found a new home in the flourishing city and captured the lively everyday life on the large Dam Square.

Some 200,000 people live in Amsterdam – but all decision-making power lies in the hands of a select few. This influential patrician elite is closely linked to the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC for short). The trading company is the driving force behind the economic success of the Dutch Republic – and its ruthless colonial exploits.

The Flipside of the ‘Golden Age’

From 1611, the city’s flourishing trade centred on the newly completed Amsterdam Stock Exchange – a marketplace for goods from all over the world. For the first time, wealthy citizens, merchants, craftsmen as well as humble labourers and even servants had the opportunity to invest their personal capital in shares.

Henceforth, people could put their money to work for them. Speculation may have involved risk, but it could also be extremely lucrative. VOC shares were a particularly popular investment choice: the private capital funded entire fleets and military companies. Moreover, the purchase of VOC shares was seen as a patriotic act and contributed to the massive economic growth of the Netherlands.

Here is the stock exchange, and the money, and the love of Art.

Thomas Asselijn, 1654

Right next to the entrance to the inner courtyard of the stock exchange, an art dealer is offering his wares. Nowhere is the economic boom more evident than on the art market: at its peak, some 70,000 paintings a year were flying off the easels in the Dutch Republic. This period would go down in art history as the ‘Golden Age’.

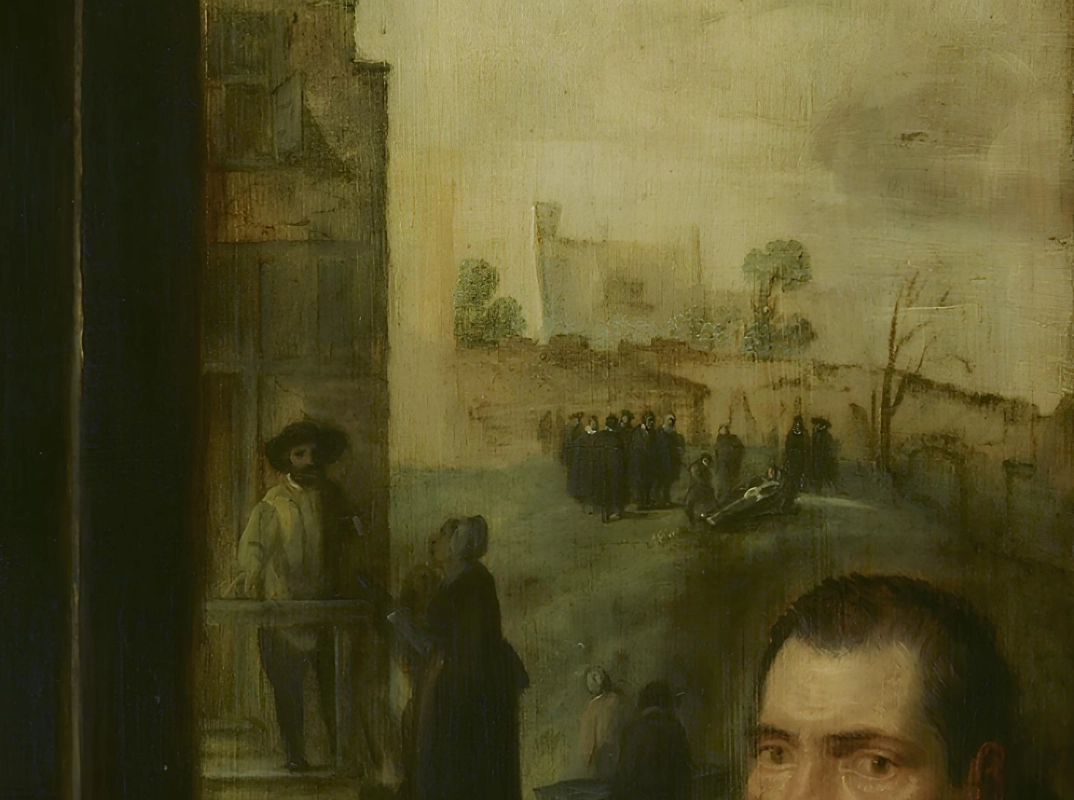

Rembrandt, too, was drawn to the thriving metropolis and moved there in 1631. His reputation as an excellent painter and graphic artist preceded him. He quickly built up a network of influential patrons. With vivid portraits like the one shown here, he demonstrated his skills to his clientele. The name Rembrandt became a brand – a synonym for first-class art.

DEFENCE AND ORDER

Not accessible to everyone: only those who can finance the weapons for the influential civic guard companies themselves are accepted as members. These exclusive associations of men can be depicted in representative paintings. The militia guilds gave rise to the civic group portrait: a pictorial genre that flourished nowhere else to the extent it did in Amsterdam.

Cornelis Anthonisz stages the city’s militia company in their gleaming armour like a defensive wall – shoulder to shoulder, in rank and file. This stylistic device recalls the traditional portrayal of donors in paintings of saints: before God, all believers are equal. However, the implied equality is deceptive. The militia guilds were subject to a strict hierarchy.

Honour, Duty and Hierarchy

It may be the most famous schuttersstuk in the world, but only a few people know that Rembrandt’s The Night Watch shows an armed company of arquebusiers setting out on patrol. The task of Amsterdam’s schutterijen was not only to defend the city against enemy attacks from outside – they also preserved order within the city.

Rembrandt resolutely breaks with the rigid compositional formulae of earlier group portraits and shows the kloveniers going into action. The dramatic picture is so impressive that it is copied several times shortly after its completion.

And commissioned to paint these figures were not the worst masters, but ones who were consideredleading lights of the arts.

Johannes Isaacsz Pontanus, 1614

The doelens, the lodges of the militia guilds, had large banqueting halls that were grand enough to serve as assembly rooms for the city council. The magnificent group portraits that adorned the walls reflected the wealth and power of Amsterdam’s citizenry.

Four former officers sit for a group portrait showing them in their new roles in 1655. As wardens of the Kloveniersdoelen, the arquebusier guards, they now assume prestigious duties in the city administration. Their elegant black clothing sets them apart from the host and his family who are dressed in simple linen. The wardens are wealthy, respected and Calvinist – the prerequisites for holding any honorary office in Amsterdam.

One city, many faces

A look behind the glittering facade of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ reveals that it conceals a distressing social inequality.

The family of a blind hurdy-gurdy player goes from door to door asking for alms. Rembrandt’s prints shine a light on the poor, the sick and the old. The artist allows us to catch a glimpse of the life and everyday reality of those whose wretched existence was rarely deemed worthy of artistic attention, let alone the price of a print.

The poor and sick are usually banished to the outskirts of Amsterdam. Only once a year are they put on display in a ceremonial parade on the central Dam Square to raise funds for the city's aid organisations.

This ostensibly candid view of Amsterdam is in fact a carefully staged construct. Painted in 1633, it was commissioned by Leprozenhuis. They ran the institution for people suffering from leprosy and sought to showcase their charitable work and importance within Amsterdam’s society.

From rat catchers to regents: In 17th-century Amsterdam, everyone knows their place. A strict social hierarchy structures the communal life of the city. The predominantly Calvinist population of Amsterdam firmly believe in a predetermined destiny. Prosperity is seen as a sign of divine grace – poverty as a test of faith. The relationship between rich and poor is seen as God-given. Social advancement is almost impossible.

Social welfare was traditionally a task of the Catholic Church. When the Calvinists came to power and the population grew rapidly at the same time, an enormous challenge arose. From then on, the city administration had to take over charitable activities itself.

Amsterdam’s first orphanage was founded by wealthy citizens around 1523. In 1580, two years after the Alteratie, the institution took over the premises, lands and assets of the dissolved Sint Lucienklooster. The institution was funded by regular rental income as well as tax revenue and donations.

New Values - New Ways of Thinking

Republics that valued their capable citizens, most highly devoted the greatest attention to the education of their children.

Johan van Beverwyck, 1664

The six regents of the Citizens’ Orphanage (Burgerweeshuis), are gathered around a desk. Several children are brought before them for registration. This institution catered solely to the orphaned children of Amsterdam residents who had enjoyed burgher status. Their children were cared for, schooled and raised to become useful members of civic society.

The male regents oversaw the registration of orphans, finances and upkeep of the building. Unusually for the time, women also took on leading positions as ‘regentesses’ of charitable foundations – albeit with limited powers and no opportunities for advancement. They were in charge of domestic matters such as hygiene and the provision of food and clothing.

At the heart of the composition but of no consequence: a girl is brought before the regentesses of the Citizens’ Orphanage (Burgerweeshuis). All the wards are carefully registered in a large book. The names of the regents have come down to us – that of the child has not.

In the 17th century, the Citizens’ Orphanage alone was home to some 700 to 1,000 children. Wars, epidemics and the rapidly growing population had dramatically increased the level of poverty and destitution in Amsterdam.

Profitable Charity

Several institutions took care of Amsterdam’s orphans. Founded in 1657, the Diaconia Orphanage accommodated Protestant children whose parents did not have full citizen status. Meanwhile, the Almoner Orphanage had been taking charge of the children of impoverished parents. In the Citizens’ Orphanage, conditions were relatively good: while the children here had to share their bed with just one fellow orphan, in other orphanages up to five children had to sleep in a single bed. At the Diaconia Orphanage, there are not nearly enough soup bowls for every child.

Broadly diversified, the system of charitable foundations offered support to the vulnerable and destitute. At the same time, the strict admission policies and discrimination along confessional and class lines reinforced the rigid hierarchical structure of Amsterdam’s urban society, which was almost impossible to break through.

Conditional Relief

The goal was to eliminate poverty from the urban landscape: a ban on begging came into force in Amsterdam in 1613. That same year saw the foundation of an almshouse, the Aalmoezeniershuis, to assist those who had fallen on hard times through no fault or moral failing of their own.

Feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, caring for the sick or burying the dead: Pieter Aertsen depicts the seven works of mercy. This Catholic pictorial theme of Christian charity is echoed once again in a work by an unknown artist. In Calvinist Amsterdam, it was only possible to draw on the Catholic pictorial tradition in the almshouse. Only here were the governors allowed to be Catholic.

An eye-catching ruff and richly brocaded silk: the black garb of the almshouse governor is in line with the relatively modest dress code of Calvinism – and yet the sophisticated detailing attests to its elaborate manufacture.

The luscious deep black contrasts sharply with the drabness of the worn-out clothing of those seeking help. As it was forbidden to go begging from door to door, they hope to be given new garments at the almshouse. Anyone caught begging faces the risk of forced labour, for example in textile production.

Statement Fashion

Strict conditions: the six governors of the almshouse only provided support to the so-called ‘deserving poor’. According to their understanding, these were people who were destitute but willing to work and who came from Amsterdam or had lived there for at least three years. Only if these criteria were met, the sick were treated in an infirmary or isolated to contain the spread of contagion. And anyone registered as a transient could find temporary shelter in the almshouse, as could the children of tradespeople who were apprenticed in Amsterdam.

During home visits, the governors ascertained that the recipients of alms were, in their opinion, indeed worthy of the support they received: if they deemed the claimant’s destitution to be the result of idleness or dissipation, they would rigorously refuse all forms of support.

Seriously ill, but still making an effort: the painting offers a glimpse of a humble Dutch home. The general buzz of industrious activity makes it clear that the inhabitants are very much ‘deserving poor’ who have fallen on hard times through no fault of their own and thus warrant support.

If you look closely, you will find the almshouse performing yet another charitable act on the right-hand edge of the painting: the burial of those who cannot afford a Christian funeral.

Help with Conditions

The gap between wealth and poverty is wide in Amsterdam. Over the course of the 17th century, the concept of charity and indigence also changed: the existence of poverty is necessary so that influential citizens can show off their charity. Their meritorious giving enhanced their own prestige and preserved the status quo of the social order. By logical extension, therefore, in this system the complete eradication of poverty cannot have been the ultimate goal.

A more humane penal system? Only at first glance. From now on, minor offences will be served in prisons. But the institutions also pursue economic interests. Despite these reforms, the death penalty was not abolished. Without scruples, those executed are deprived of the peace of the dead and their corpses are made available for research.

This sight is almost unbearable: the bodies of executed criminals were displayed along the access road to Amsterdam – as a brutal deterrent. At the same time, the gallows field was a place of public spectacle. Featuring food and drink stalls, it attracted curious onlookers. Nor was it unusual for artists to come here to draw lifeless bodies.

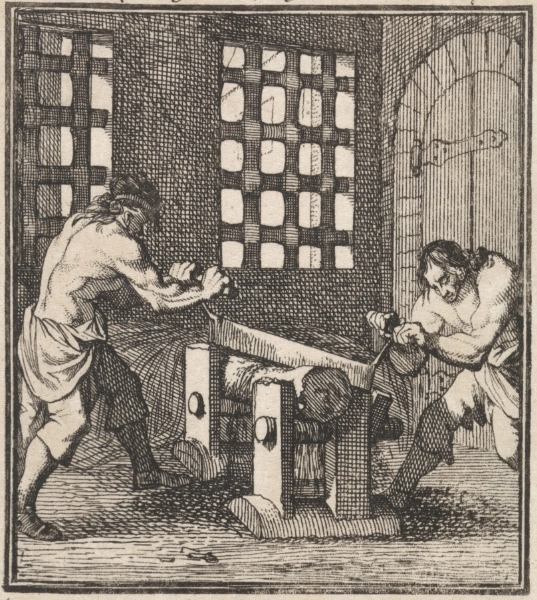

In Calvinist urban society, the benefit to the economy and society has top priority. As the centuries-old brutal practice of corporal punishment, such as mutilation or branding, led to a reduced ability to work, a reform of criminal law was required. So, the Rasphuis, the first prison-workhouse for men, opened in Amsterdam in 1596.

Discipline and order reign supreme. The sculpture of Castigatio, the personification of Chastisement, watches over the inner courtyard of the Rasphuis. The regents attend to the business of the prison-workhouse in the institution’s boardroom. They impose strict discipline and hard labour to guide offenders back onto the right path.

Criminal Law in Transition

The regents' commercial interests were driven by economic considerations; the inmates were a source of cheap labour. The harshness of the penal system in the Rasphuis is almost unimaginable.

A punishment more bitter than death.

Dirk Volckertsz Coornhert, 1587

A feat of strength behind bars: two men are laboriously rasping a log of brazilwood. Known for its hardness, the dyewood was imported by the Dutch from colonised Brazil. The finely rasped shavings were used to produce the valuable brazilin, which was used to dye textiles. The regents of the Rasphuis held a monopoly on this process.

Turning the inmates into ‘better’ people involved not only continuous hard labour, but also religious Calvinist instruction. Weekly attendance at church services was compulsory for the inmates of the Rasphuis.

Curiosity and Warning

A rare sight – female and male governors (‘regentesses’ and ‘regents’) on an equal footing in the same painting. They jointly ran the Spinhuis, Amsterdam’s prison-workhouse for women. During their weekly meetings, they discussed financial matters and the quality of the needlework produced by the women prisoners.

The harsh everyday life at the Spinhuis is suggested in the background. Most of the women were convicted for begging or prostitution.

The Offence of Prostitution

Dressed in sober, respectable clothes, their hair neatly done, the convicted women are exposed to the curious gaze of onlookers. The everyday life of the women in the Spinhuis is filled with sewing, knitting and spinning.

These activities have great symbolic meaning – in classical mythology, Penelope whiled away the years until the return of her husband Odysseus by weaving. In 17th-century Amsterdam, too, patient needlework symbolised the virtuous fidelity of the housewife.

The founding of the prison-workhouses in Amsterdam ushered in a new form of penal system. However, it was not until 1870 that the death penalty was abolished in Dutch criminal law.

Death for Science

The harshest punishment: those condemned to death are denied a Christian burial. This not only robs them of their final shred of dignity but also, according to Christian belief, of any chance of salvation. Some of the bodies were presented to the surgeons’ guild for anatomical research.

The Amsterdam master surgeons (or rather ‘barber-surgeons’) are shown gathered around Dr Sebastiaen Egbertsz, who is holding a pair of scissors to perform a dissection on the corpse lying on the table before them. At that time, no Christian would have agreed to a voluntary body donation. But, as the doctors conveniently agreed, the soul of an executed criminal was beyond saving anyway.

Skins teach without voices. Mortal remains though in shreds warn us not to die for crimes.

Caspar Barlaeus, 1639

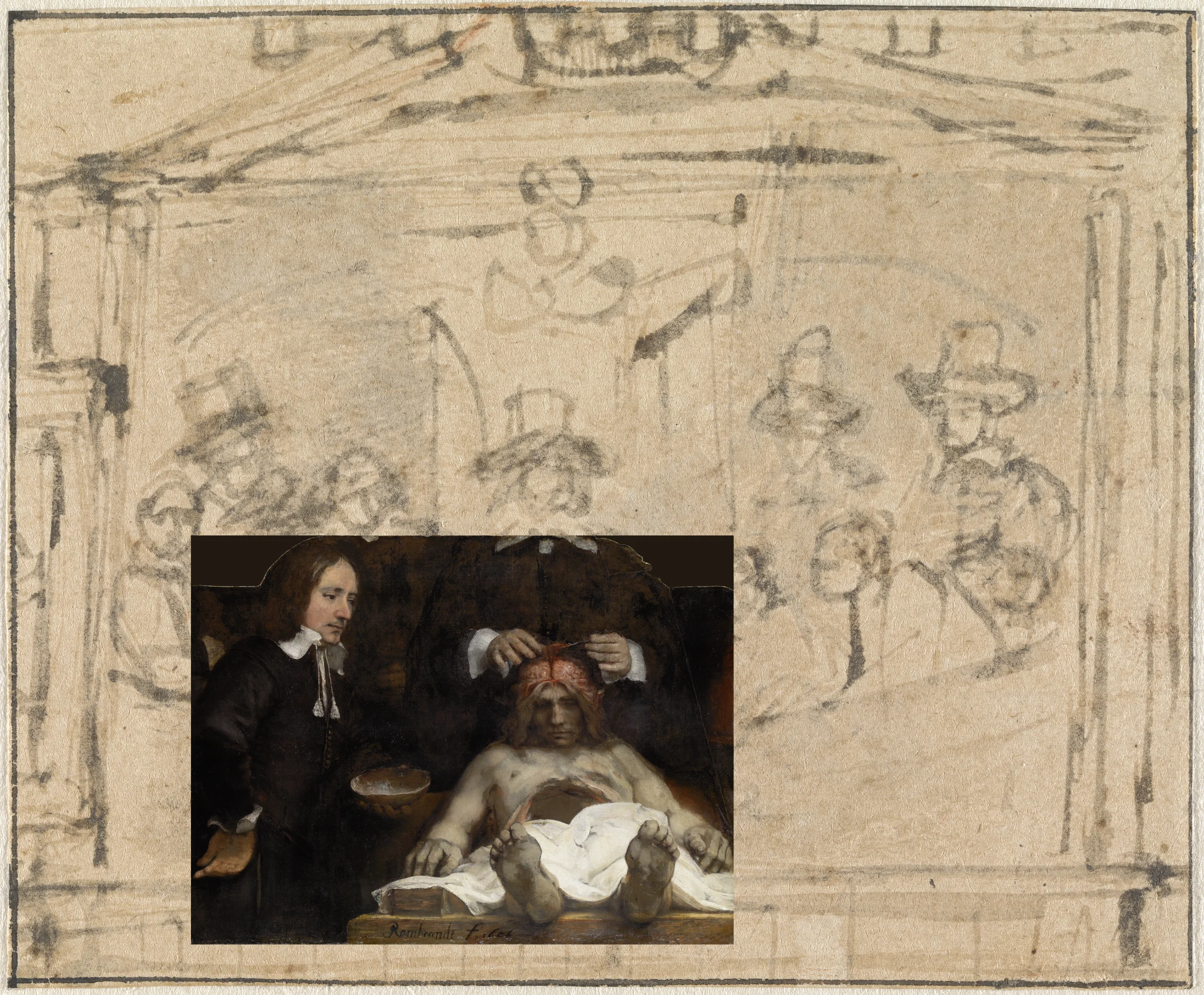

Once a year, the master surgeons were given the opportunity to acquire fundamental insights into the human body at a public anatomy lecture. There was great interest in the lectures – for a fee, even non-medics could attend the autopsy. The annual event of the surgeons’ guild thus offered a somewhat macabre way of attaining knowledge.

An Insightful Gaze?

Five surgeons have their portrait taken with the lecturer, Doctor Egbertsz – not a surgeon and not a guild member, but an academically trained physician. At the heart of the composition is the skeleton of an executed English pirate.

Twice a week, lessons were held in body morphology and osteology. By attending, surgeons sought to uphold the quality of medical care. More complex operations were performed exclusively by academically trained physicians. Surgeons, on the other hand, carried out minor procedures, such as bloodletting, in their practices throughout Amsterdam.

The Surgeons’ Guild commissioned this group portrait from Rembrandt, even though he was already past the peak of his career. He was supposed to portray the doctors at Dr. Jan Deijman's anatomy lecture. Today, parts of the painting are missing – much of the canvas was destroyed by fire in 1723. The surviving preparatory sketch gives an idea of how large the painting once was.

Rembrandt places the corpse with its face towards the viewer and gives it portrait-like features. In this way, the dead body appears to be given a soul again. The artist presents his own interpretation of the autopsy with great sensitivity. The staging of the executed man makes us aware of the finite nature of our own lives.

Rembrandt died in poverty in 1669. Around the same time, as public funds were severely strained by wars with France and England, Amsterdam’s economic boom came to an end. Despite this, the Dutch Republic remained the world’s richest region until the end of the 18th century.

In outstanding paintings, we encounter the economic boom of Amsterdam in the 17th century. However, on closer inspection, the impression of a flourishing past has a painful flip side: a darker story that speaks of poverty, oppression and exploitation.

EYE CATCHER

Hot fat and sweet batter: lured by the irresistible aroma, a crowd gathers around a woman making and selling pancakes in the middle of the street. The few, generally affordable ingredients made pannekoeken a favourite treat for everyone. Rembrandt’s sensitive etching captures a fleeting moment of happiness in an otherwise harsh environment. He skilfully juxtaposes intricate, dark web-like textures with barely suggested details: the pancake woman forms the calm centre of his composition.

Sponsored by

This Digitorial® was developed by the Städel Museum, Frankfurt/Main, with kind support of the Deutsche Börse Group. Digitorial® is a product line of the Städel Museum.